In Cahoots

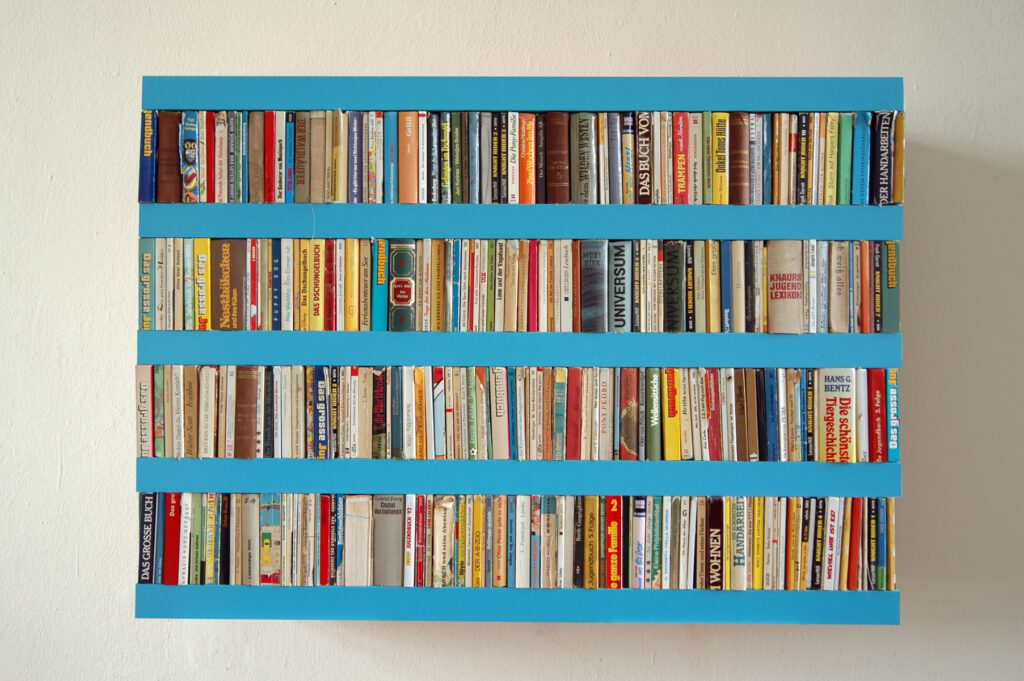

Takadanobaba is the display of the entire contents of the cramped Australia Council’s artist residency in Tokyo. This mass is the result of successive individuals caught up within the initial excitement of a hyper consumer society. The build-up is perhaps due to their short-term habitating cycle of residence within the space. These material dispossessions are stacked in some kind of order, attempting to create space within confinement.

The stack is constricted within the dimensions of the room. The room is also constricted within the dimensions of the tatami matting- as seen in the foreground of the picture. This articulation of dispossessions confined by space and time mirrors the desire to create a distinct personal identity within the multitudes of the metropolis.

The question of whether these left behind items are of practical use for future residents remains. A sword made of wood, a guitar left unstrung, things that do not make it to souvenir status become the detritus of a shifting space. These objects create a barrier or wall of sorts. Through the acquisition of these objects were the owners brought closer to the society that they found themselves in? The work questions the link between the possession of materials and personal identity.

Maintenance

Living in the city is a very convenient thing indeed. One of the most convenient things about living in the city is garbage removal. When we moved out of our home in Ashfield, New South Wales, we threw out two tonnes of garbage. This was accumulated in only 24 months of living there!

This wasn’t garbage, like beer bottles and decaying foodstuffs. Most of it was old artworks and dilapidated furniture. We aren’t wasteful art-collecting furniture-trashers: it’s more like a lot of the art we made and furniture we found had merely taken a detour through our house on its way to the garbage heap.

The great thing about throwing things away is that their existence disappears from your mind: into landfill and out of your sense of object permanence. If you are “tidy”, you don’t need to hang onto anything that links you to your past or reminds you that the laws of entropy apply to you.

Sculptors have a bad reputation for being hoarders. Even the slick design-orientated installation artists of the 21st century have a habit of picking up pieces of trash from the side of the road. The same could be probably said about farmers. They don’t seem to throw much away. There seem to be limitless possibilities within the junk heaps of farmers. Something useful may be found in deceased cars that are more iron oxide than automobile, or the old farm homes inhabited by pigeons and their poo.

The thing about objects stockpiled on farms is that they do not remain in stasis. Due to the scale of farming technology, if an object such as a plough or seeder is no longer useful, it will not be stored in a room or warehouse. It will be kept outside for future use.

But how far away is that future?

Discarded things left on farms aren’t like the trash we get rid of in the big smoke. As city slickers, we throw away stuff, and that’s the end of the story. The object’s life is over for us. Waste management systems – recycling or landfill – are invisible. Discarded objects are erased from our future.

Stuff found on farms linger. After they have been thrown out, these objects take on a whole new life.

When we came to Ballidu, it was the end of dry season. Everything seemed dead. The grass was sun-bleached and almost white. The tree branches were dry and withered. You could feel nature’s power, but not in the usual sense of verdant greenery or treacherous fauna. We could feel nature’s power against man. Our sense of time shifted to something more like geological time: slow and fast at the same time, a timescale dwarfing Human Enterprise. We were paddling boogie boarders in an ocean.

As far as we could see, we witnessed human endeavour under the immensity

of natural forces. That little tyke with his finger in the dike: human creations in need of vigilant protection from the elements, nature slithering out to reclaim them whenever we turned our backs. We could see this natural force in all the disused objects around us: tyres with grass growing out of their rims, spider and spiky lizard-infested nests in old wool-bale machines and woodpiles.

We could see this force because the past was not put out of sight.

The abandoned house on Milaby farm appealed to us most. It seemed a natural starting point. The home is the membrane between man and nature; its doors and windows the most obvious delineation between the spaces of man and nature.

Within Maintenance, we violated this junction point. Shapes extruded from the portals of the house desecrated the holy junction between inside and outside. We used Buddhist-orange, highly geometric shapes to describe a force of nature to escape a sentimental, anthropomorphic understanding of these forces. We hoped to describe a power comparable to that of the wasp impregnated within insect larvae.

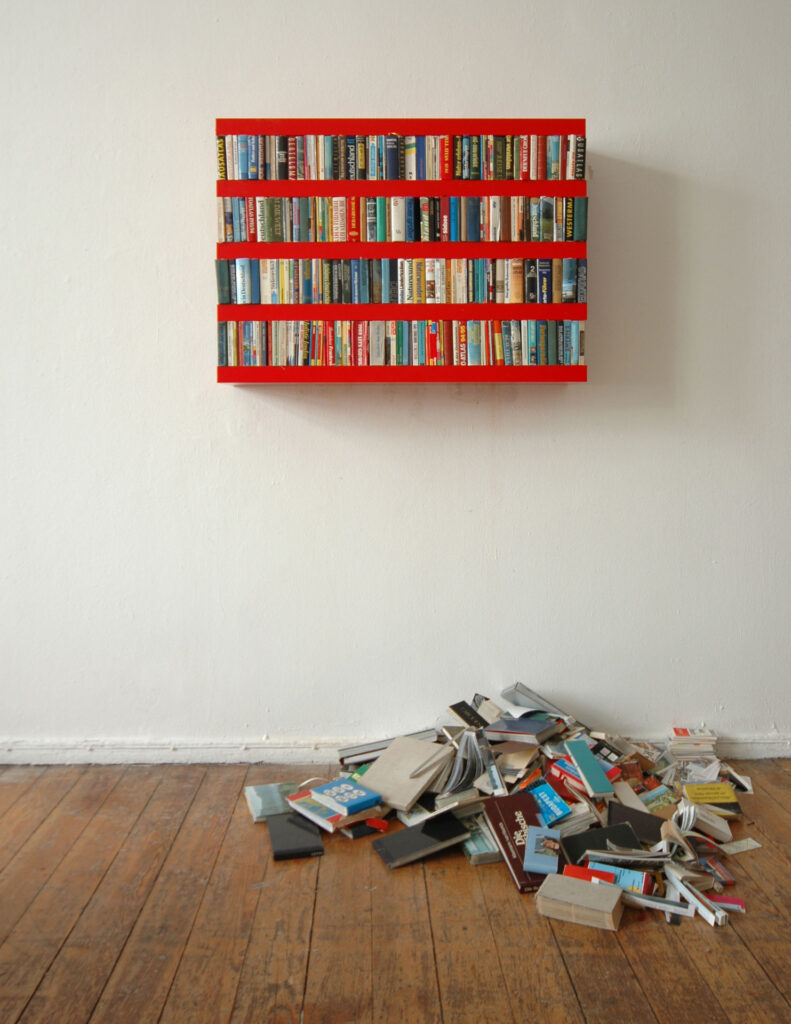

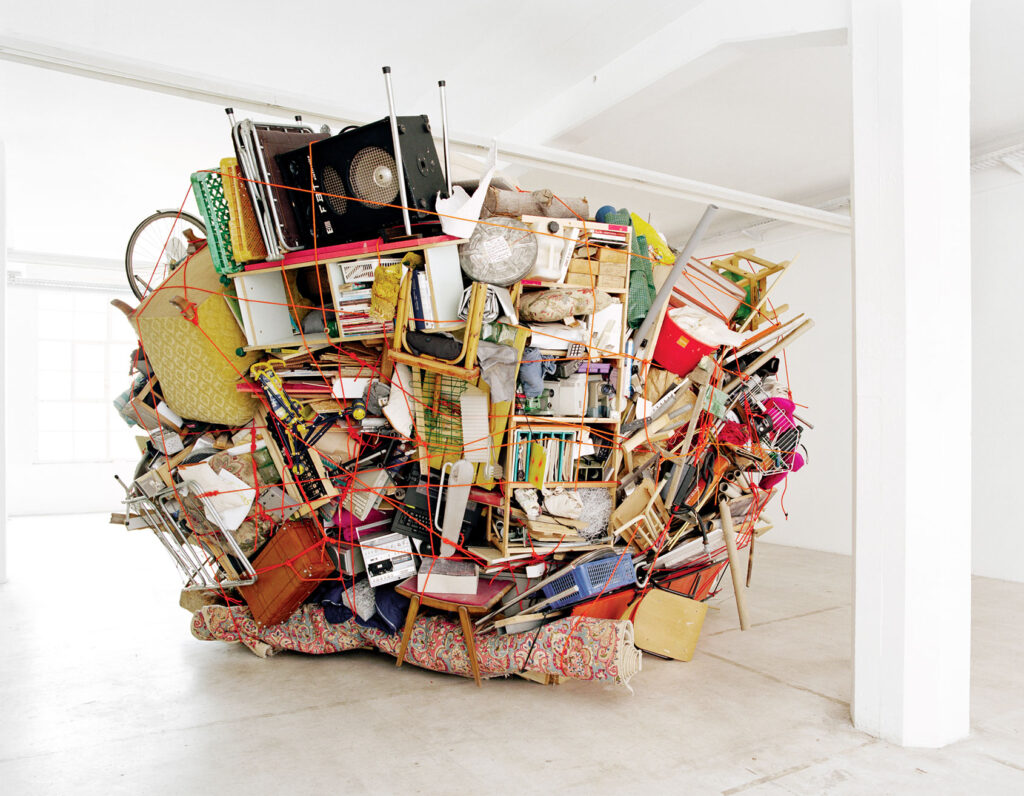

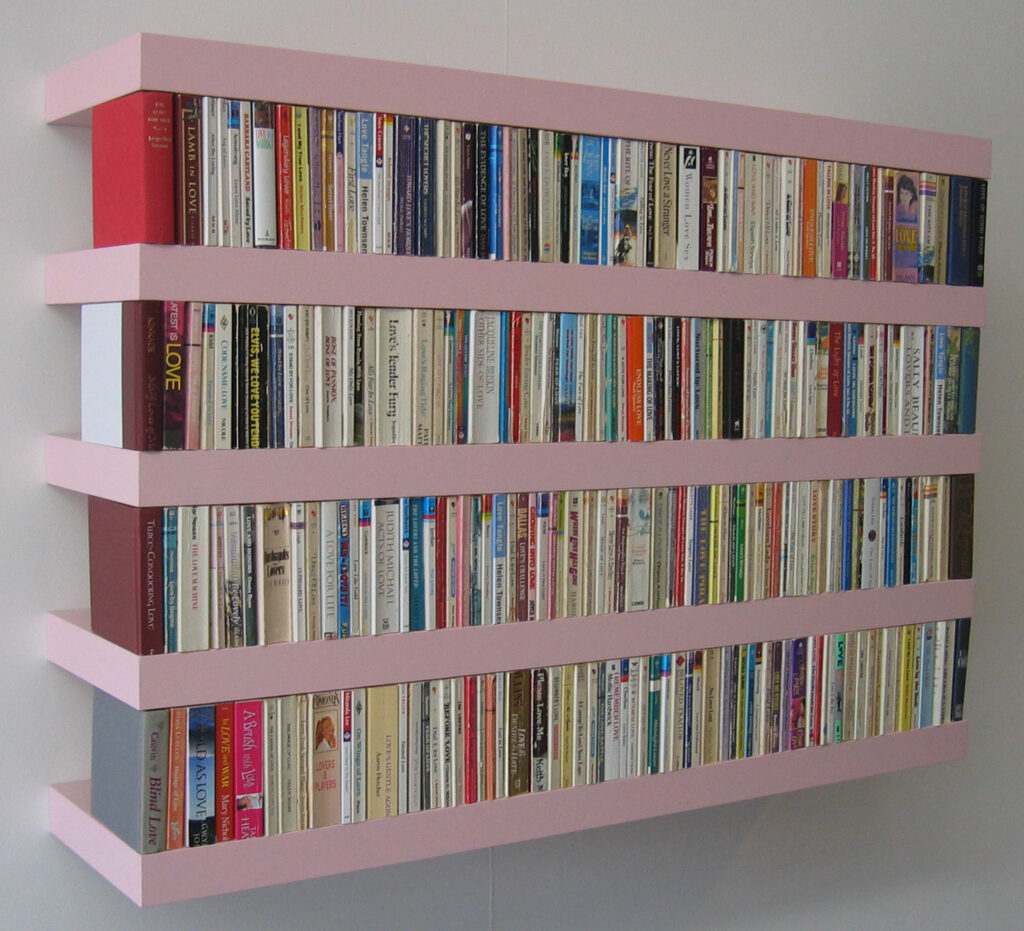

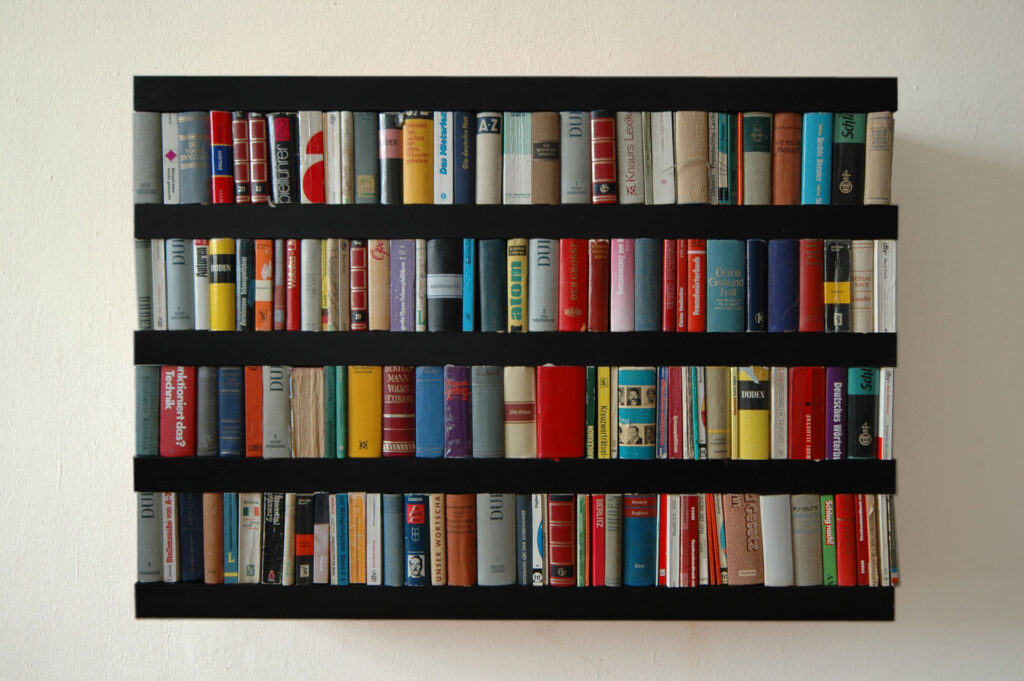

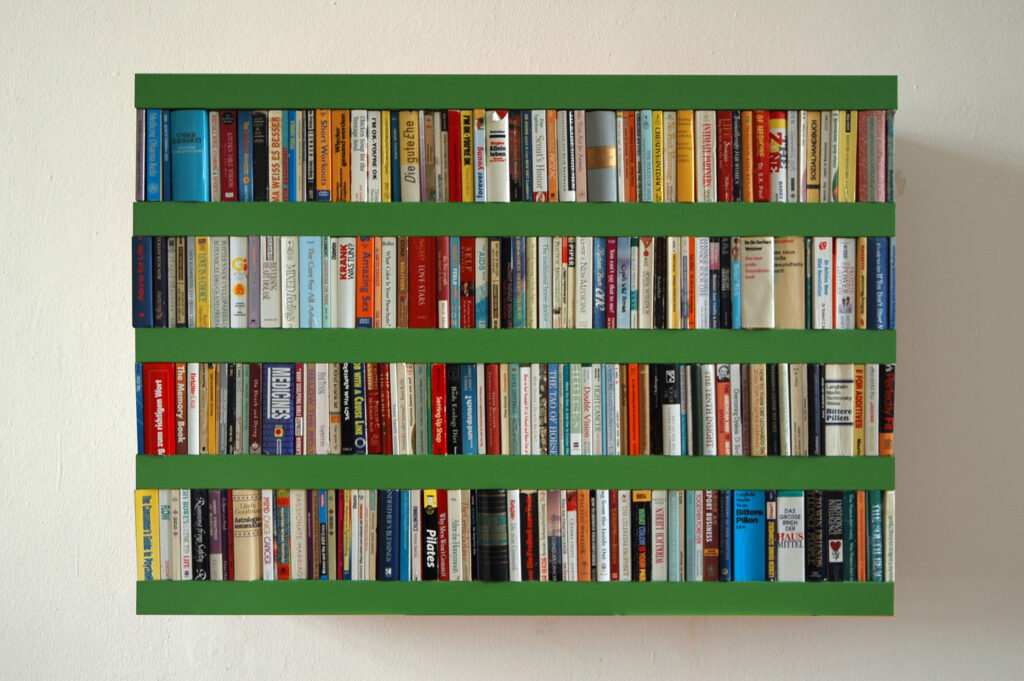

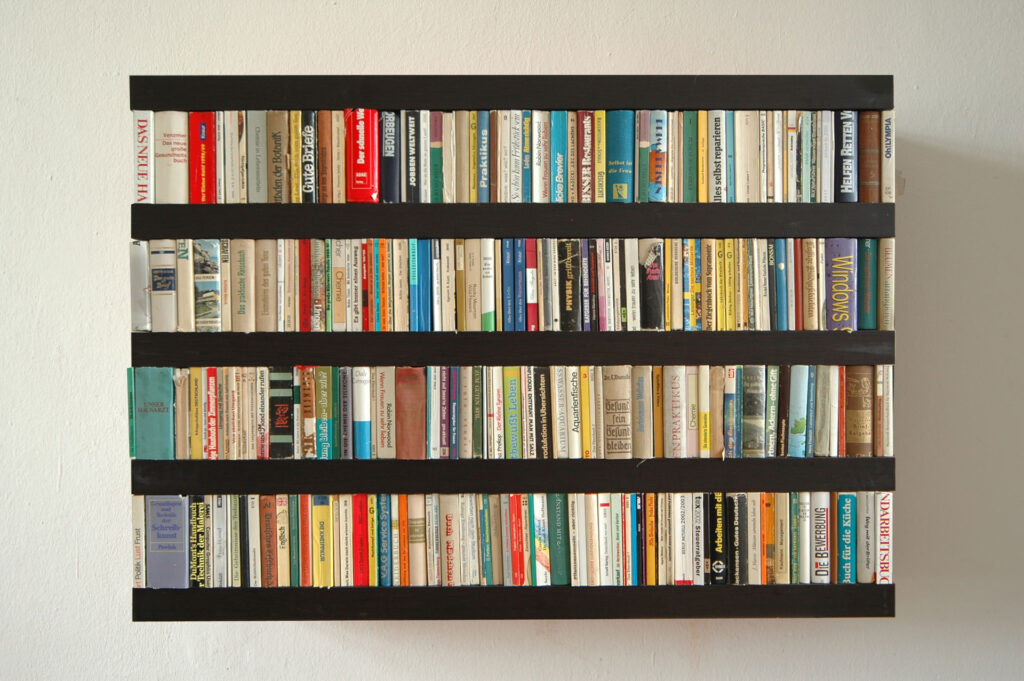

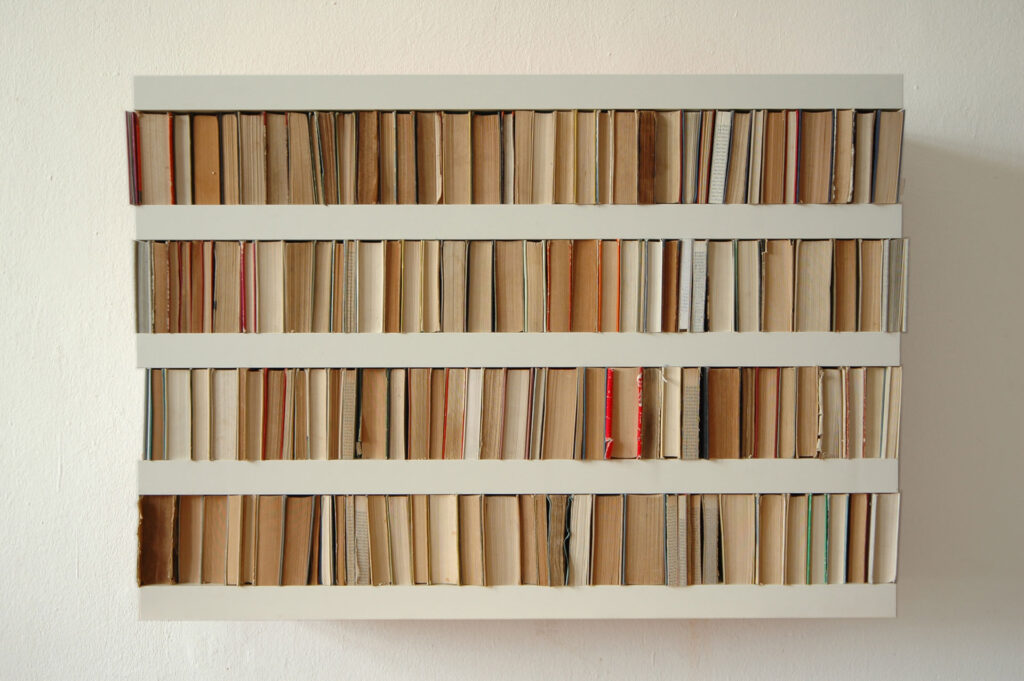

Deceased Estate

The original plan for deceased estate involved the acquisition and sculptural manipulation of an entire individual’s deceased estate. The idea was to join the objects together using rope, thereby creating a giant ball of “stuff”- similar to a ball that a dung beetle might make with cow poo. The concept was a sculptural meditation on the materials which we collect in our lives, a description of who we are or would like to be.

The idea seemed like a natural extension of a previous work- the cordial home project. Much of the strength of the cordial home project lay in its articulation of its sculptural mass. Although a house is a highly psychologically resonant object, the exhibition of the reconfigured object didn’t seem to be an overly voyeuristic exercise.

The more we thought about the premise behind deceased estate, the more unsettling it became. Although we still believed in the proposed object in a formal sense, the idea began to seem like a first year artwork (the one where you find an old suitcase full of stuff at the junkyard and do something cool with it and a bottle of shellac) with a professional budget. The entire collection of a dead person’s belongings exhibited by a pair of artists seemed too vampiristic. The more we thought about it the more it seemed like a bad idea.

A great source of much of our work probably lies in our traumatic experience of moving out of a warehouse in Surry Hills. Not that living there wasn’t fun. But when we got out of the imperial slacks warehouse we had to tear apart the entire inside of the building, leaving just an empty shell. We had to do this as a compromise with our landlord, rather than paying alleged rent in arrears. It wasn’t all that bad as most of the material was recycled into the warren lanfranchie memorial discotheque. But it was a sad thing to do, tearing apart our own home. The most stupid part was tearing apart a wall of our room. Inside the wall, we found a water tap attached to the struts of the framework. This would have been very strange and mystifying experience had Sean not put it there three years previously in the hope of puzzling the individual who would tear down the wall in the distant future. Einsterzende neubaten!

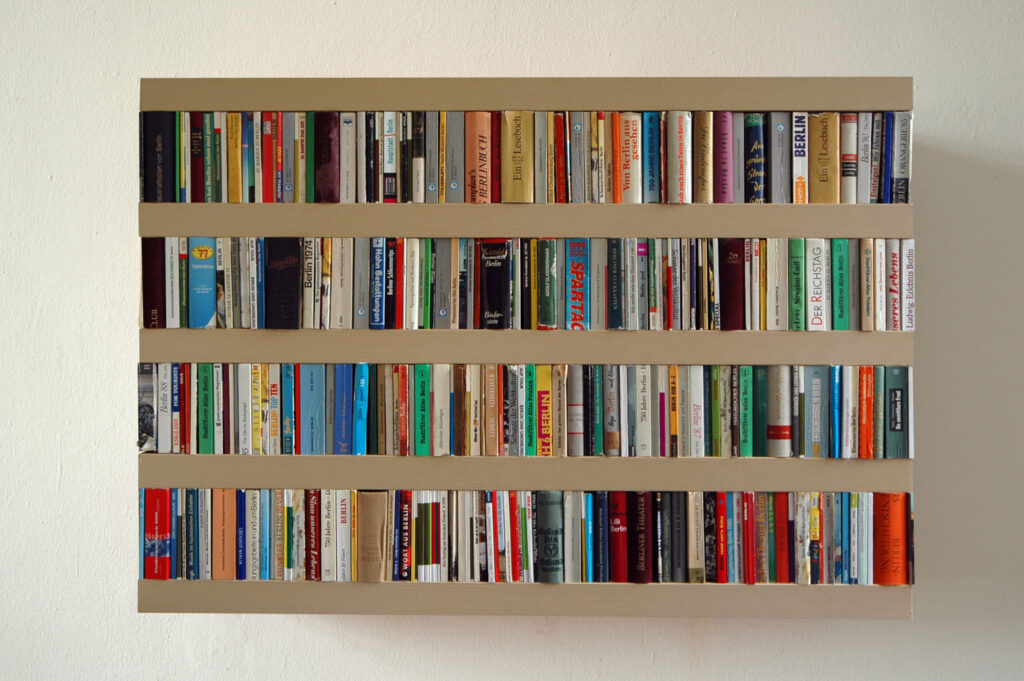

The violent act of tearing apart your own home before its time is maybe a universal experience for artists. Any artist worth their salt will be able to give you a tale of warehouse paradise lost over a glass of cab sav at a gallery opening. It’s the same old story combining post-industrial building, artists and real estate investors (you probably know who wins that story). This year we were really lucky to be able to stay at the glasshouse, an old textiles warehouse on the Rhine River, situated on the meeting point of France, Germany and Switzerland. Of course it was too beautiful. Massive glass windows, the river literally at your doorstep, close to the supermarket. It was a speculator’s wet dream. Its days were already numbered when we got there. Most of the artists had already moved out, making the decision to jump rather than be pushed out. So we had the world’s biggest bedroom- one thousand square metres! With only a futon, desk, lounge chair, two backpacks and dirty clothes to fill it.

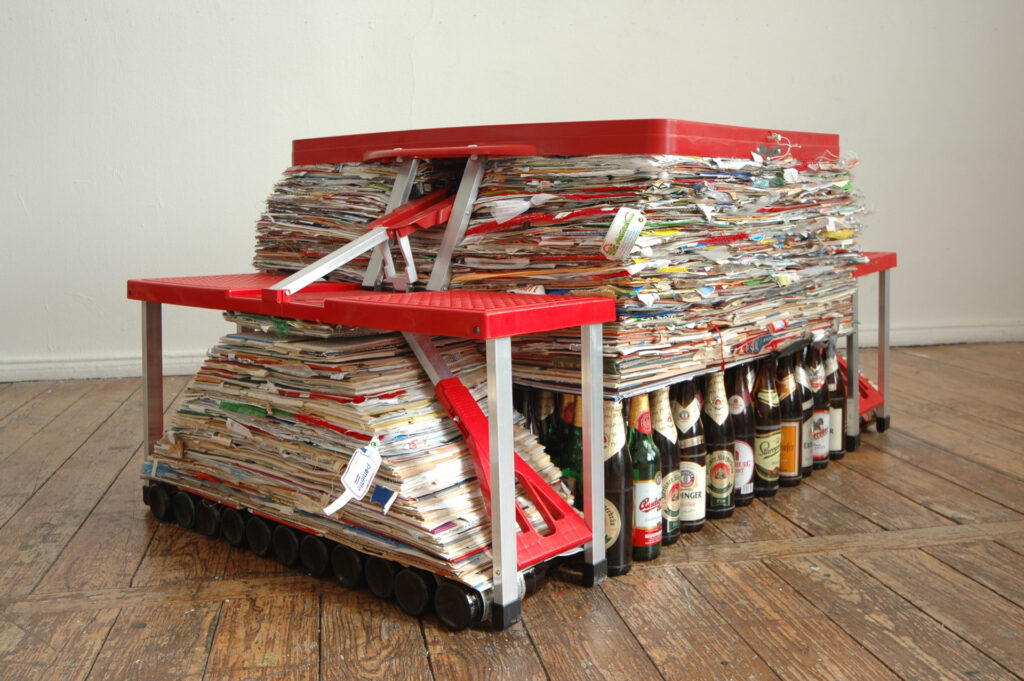

Downstairs, next to the gallery that had never had a single show (a sad combination of troubles with the landlord and artist ego), in the foyer was the detritus of four floors of disgruntled artists. Bits and pieces of stuff- furniture that was too big for their new residence, old artworks that didn’t work out, beer bottles, boxes of unused paints, reams of virgin drawing paper, magazines, lots of wood. We would pass this pile everyday to get to the elevator. Sometimes we would take a bit of wood out to burn on the barbecue or take an extra chair to sit on. Sometimes we’d add a bottle or two. It really was a great shit pile. A testament to the paradoxically high standard of living artists enjoy in the west and their chronic lack of housing stability.

As usual, it wasn’t until we had moved out that we realised the connection between the Rhine warehouse and our original idea of deceased estate. The contents of the foyer were essentially the contents of a deceased estate! Unlike the original plan, the contents of the ball, its location and the artists who put the work together were intrinsically linked.

Thus deceased estate was surreptitiously created, in an empty warehouse, in a gallery that never was, by two artists who never paid any rent there!

The plastic menagerie (2006) 300.0 x 230.0 x 195.0

pine vitrines and inflatable animals

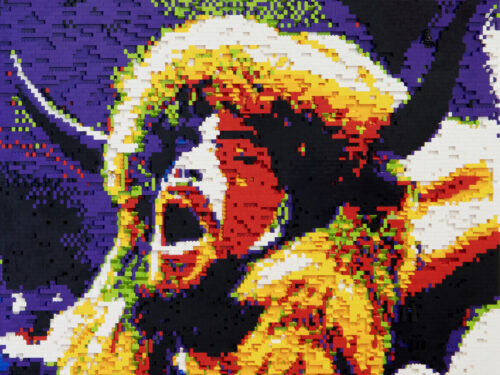

In The Plastic Menagerie Sean Cordeiro and Claire Healy continue their conceptual and material interrogation of habitat. Part of a generation who can only dream of home ownership, their work questions our attachment to place and property. In this work they have collaborated to construct a nest of museum showcases or vitrines and housed within each vitrine is an animal shaped inflatable toy. Among the menagerie, a wide-eyed Orca whale and a smiling crocodile speak of our incessant taming of the world and our absurd tendency to anthropomorphise even the most exotic beast. The vitrines are stacked on top of each other in a manner more reminiscent of pet shop chaos than the order of a natural history museum. This controlled chaos connects The Plastic Menagerie to their earlier work featuring the act of deconstructing and reconstructing familiar objects within the gallery space.

Each vitrine in The Plastic Menagerie is made from laminated pine, the type of material used to make inexpensive, ubiquitous furniture. Rather than the elegant handcrafted vitrines of the museum, these ‘storage solutions’ have a certain DIY appeal. Is it possible that the work is supplied as a ready to assemble animal menagerie where the animals can be inflated and safely housed within their flat-pack vitrines?

Installed within a manner of minutes, this menagerie offers a portable and compact living solution to zoo overcrowding. The Plastic Menagerie also offers a possible panacea to curators and collectors who can assemble at will their own museum collections. But what of the decline of the species wrought by slow leakages and sagging plastic? Are these creatures doomed to become deflatables? Unlike the broken glass animals that symbolise a young woman’s awakening to the perils of the world in Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, this plastic fantastic inflatable animal kingdom offers a certain resistance to reality.