Doillies of Terror

Ten[d]ancy 2006

Martin Blum, Sean Cordeiro, Simone Fuchs and Claire Healy

The story of Elizabeth Bay house is often portrayed in the style of Jane Austen, as exemplified within the publication Macleay Women: Taste and Science. The Macleay story is played out as the intellectual family with many daughters, who find themselves in hard times, much like the characters of Pride and Prejudice. Of course, the reality of the situation is much more complex and funny and troubled than this but maybe it is a helpful device to use existing familiar narratives to understand the past.

This is especially true within a house museum. In a house museum we are invited to investigate the stage in which some kind of drama has been played out but we must use our imaginations to reconstruct the actions that conceivably took place within the walls. Hitherto, there has been a heavy reliance on the period dramas of Dickens or Austen to help the audience unravel the story of Victorian era Australia. This is only natural, with the help of these novels and their subsequent film and televisual adaptations, we can imagine the individuals that inhabited these colonial homes- walking around, wearing fancy clothes and talking in British accents. But the stories of these authors didn’t take place in gigantic gaols, thousands of kilometres from home, surrounded by petty criminals, political prisoners, scary black people and bizarre flora and fauna.

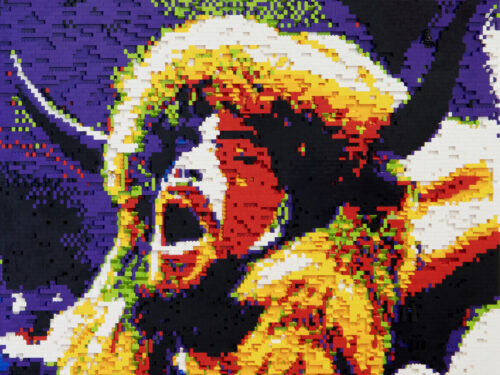

The use of Elizabeth Bay house as a site for artistic investigation is a unique opportunity to explore the emotions felt by the European inhabitants of the early colony. Current practices in museumology, perhaps as a reaction to the less informed baroque historic interpretations of yesteryear makes it difficult to interpret the past in a manner which could be considered sensational. In a response to this sanitation of history, we propose to use the narratives of George Romero as a starting point to investigate how the inhabitants of Elizabeth Bay house may have felt about their situation in Sydney.

In the late 1980s the then deputy Prime Minister, minister for finance and avid amateur historian Paul Keating famously described Australia as “The arse end of the world.” This statement was made in an age of jet travel and satellite communication. Imagine how the inhabitants of the colony must have felt about Sydney in the 1830s! Perhaps they may have just simplified Keating’s statement to “The end of the world”.

So, possibly it is not too much of a large stretch to marry Elizabeth Bay house with the genre of the zombie film: the most horrific of “end of the world” scenarios, where the main characters of the film find themselves within a paranoid world that looks like our world but which is in fact strange and lethal. The zombie film can be seen as a metaphor for colonisation. Within the zombie film the main characters (the colonisers) must first find refuge (most often by force) in a secure shelter, safe from the unwelcoming locals. Having achieved this they must also secure food and water to maintain life. Subsequently to this they must maintain balance within the dynamic of the group that they have created and finally, if they get that far, they must think of the continuation of the species.

Using the language of the zombie film, we can illustrate the heightened atmosphere of violence, mistrust and paranoia that must have surrounded the Macleay Household and the general Australian colony in the 19th Century. A legacy that we may still be experiencing to this day. Elizabeth Bay house is truly an awesome home; the fact that it was built only 50 years subsequent to white colonial settlement is testament to both the fantastic mad vision of Alexander Macleay and the excellent penal management of the British Government. By studying the architecture of the home we can perhaps glean some information surrounding how the family might have felt about living in the gaol that was called Australia. The house’s design is very much similar to a fortress. For instance the sandstone walls are more than 12 inches thick. The walls enclose the unique ovular dome, which is, in effect, a covered courtyard. Like the characters in a zombie film, the Macleays had to protect themselves from outside and from within. The family could neither trust the servants who worked for them nor the environment which surrounded them: the mezzanine servant’s quarters and the downstairs kitchen were both left unused, the former due to past silver cutlery thefts and the latter due to fire hazards not present in Europe.

The Victorian Australian feeling of fear and paranoia of the outside world will not be set up as a diametric opposition between inside and outside, i.e. European vs indigenous peoples. The question must be asked, what is a zombie? Are we actually the zombies, the future eaters, the killers of the original people? In the end, the zombie genre will be used in the instillation to question who exactly is the zombie. Who is really the undead?