Harbouring

Creating artwork during a residency is ticklish business. At the beginning, there’s always the question “What kind of strategy should we employ to create work?” There are two main possibilities: 1) Use the time and space to create a body of work that you have always wanted to create but didn’t have the optimum circumstances to create or 2) React to the space in a site-specific fashion through researching the psycho/cultural/historical nature of the location.

The first option has its merits: you can create a body of work that fits seamlessly into your artistic practice and at the end of the residency take home a bunch of work that might generate some income or some curatorial traction. But this course of action begs the question ‘why do you have to uproot yourself from your comfort zone just to make work you could make at home?’

The second option, the site-specific option, locates the work within the space and offers the possibility of some kind of knowledge expansion. The only issue with this approach is the possible development of some kind of ‘Messiah Complex’: the belief that within a few months of residing in a new space, the artist with their special vision, can gain a deep understanding of the local culture and history and provide meaningful insights to the grateful inhabitants.

Of course this is a simplification of the experience, there are other possibilities and also permutations of the two that we have outlined above. But we really were debating between these options as we began our residency at Te Whare Hera.

In the end we decided to take both options.

Our site-specific approach titled The Wrong Landscape was heavily informed by Mike Kelley’s ‘Playing with Dead Things: on the Uncanny’. The Uncanny was originally a site-specific work that took the museum itself as the site. As part of the Sonsbeek 93 exhibition in Arnhem, Netherlands, The Uncanny was a response to the post-modern practice of performing interventions in unconventional spaces. Kelley took on the role of the curator working within an institution and created an artwork that was a hermetic, curated investigation into the uncanny in contemporary sculpture. Complete with curatorial text and catalogue written by Kelley, The Uncanny was a reflexive intervention within an institution. We have taken a similar approach, to use the conventional to challenge the conventional : to use the studio as locus of investigation.

To re-iterate, the beginning point for our body of work is the studio. This may sound asinine but our practice usually has a savour faire attitude to studio and have you seen the Massey studio? Te Whare Hera is located on the end of a sparkling new wharf development in Wellington harbour. Functioning as a kind of cultural olive branch to soothe the transition of public land to private use, the international artist residency has an outlook that is second to none. Looking out the windows of the studio we can see the harbour, the shipping container yards, Lower Hutt and the mountains surrounding us. We wondered to ourselves- how often would we be in a studio situation like this? Our art practice has often influenced our lifestyle and vice versa. Gazing out at the view of the beautiful landscape from our studio windows made us think of Plein Air painting. We would become armchair Plein Air painters from the comfort of our climate-controlled studio! A trip to view the collection at Te Papa confirmed our suspicions. Landscape painting can be used as a device to attempt to make sense of a new landscape to foreign eyes.

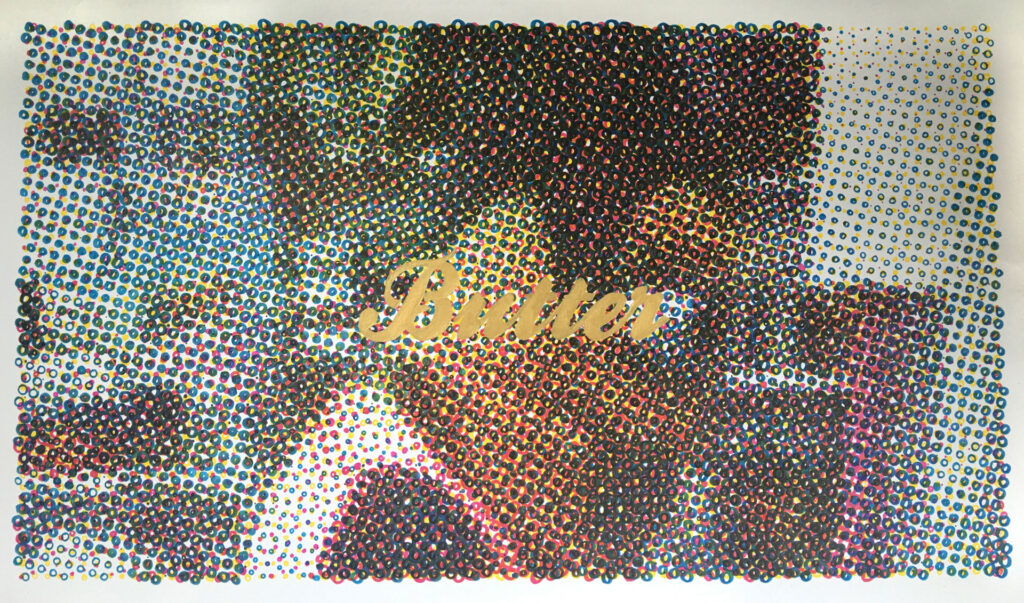

Once we decided that we would become armchair landscape painters, all we had to do was figure out how to paint… There were a couple of false starts: dabbling in camera obscura, additive colour models and reduced colour pallets when we hit upon the idea of employing the four colour separation process to make up for our lack of painting technique.

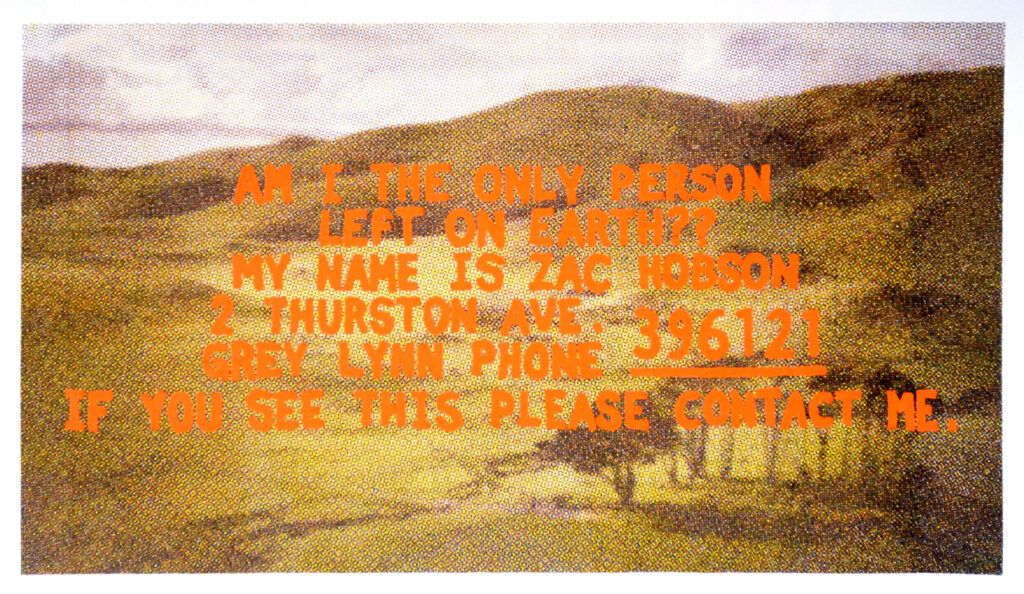

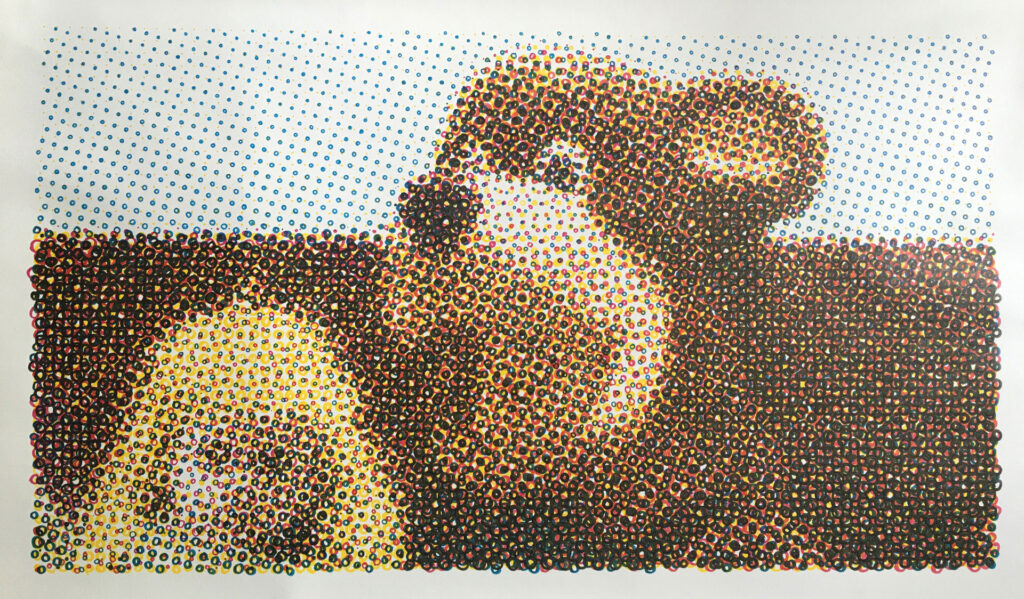

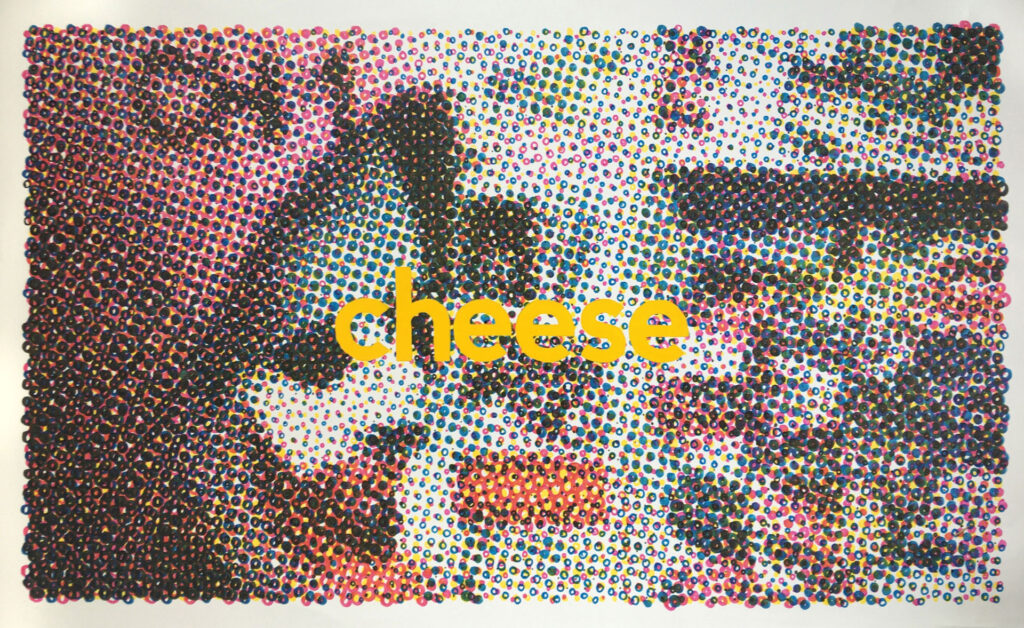

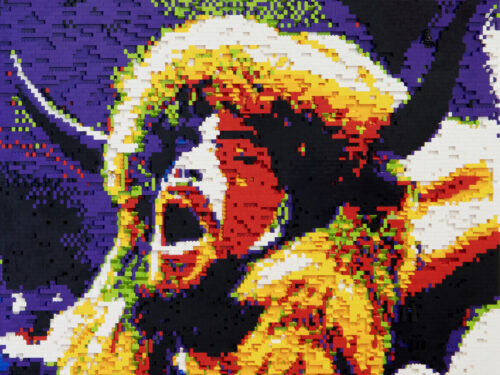

Although we consider ourselves primarily sculptor/installation artists, we have produced several bodies of work that employ colour theory to create the illusion of representation. We have previously used Lego, cross-stitching techniques and drawing pins to create these works. The process of creating these images is not unlike a dot matrix computer. Very slowly, line-by-line, we lay down the ‘pixels’ that will create the image. The four-colour separation process is also similar to this method, only each colour- cyan, magenta, yellow and black are overlaid sequentially to create the resultant colour image. Just as the creation of new tube-based paint technology made plein air painting possible, we would employ four-colour separation technology to create our landscapes. The process of creating these images is similar to the rhythms Kraftwerk created in the seventies. By imitating the repetition of the automaton they were able to create a new kind of rhythm. In this way we are attempting to create a new kind of pointillism- hand drawing the pre-determined coloured circles that create the image of a landscape.

All that remained was to choose a landscape to depict. As far as we could gather from the colonial landscapes of Te Papa, painting is an act of seeing. We wanted to see the New Zealand landscape but we also wanted to acknowledge the personal baggage that our vision carried. We could try to paint the scene that offered itself to us from the window of our studio; only it was raining and misty most of the time…

The only thing to do was to continue our reliance on the found object while recognizing our own cultural biases. At this point it’s time to come clean and admit what a massive impression the movie Bad Taste made upon our teenage minds. As Australian children we had some kind of state sanctioned ANZAC-inspired image of New Zealand but Bad Taste was our first taste of New Zealand that was actually raw. Why not create a body of work that spoke through the lens of this abject vision?

Many horror films take place in nature, or at least in the countryside. American films such as Evil Dead and Texas Chainsaw Massacre are classic examples of the ill ease felt when we leave our usual urban environment. This ill ease that filmmakers try to recreate must have been something that the original antipodean landscape painters must have acutely felt. We can imagine those early plein air painters furtively looking over their shoulders as they painted the canvases that would end up in our museums today.

So far we have rendered images from the movies Heavenly Creatures 1994, Black Sheep 2006 and The Locals 2003. The process of rendering the film images onto canvas demands laying the canvas out on a table and hours of drawing tiny circles in the four given colours. The process is exacting and much neck and arm stretching is needed. This means that while we are rendering the images we can glance up to look out the window and admire the changing scenery on offer in Lambton Harbour. The process is similar to Averted Vision used by astronomers: faint stars are more readily seen through peripheral vision rather than staring straight at them. Sometimes the best way to see something is by glancing at it.

Our other body of work Daddy Danse Macabre is a reaction to the site-specific coolness of The Wrong Landscape. We were concerned that the project might read as some kind of gothic opportunism on our part. There’s nothing worse than a 40-something year old with a case of teen angst.

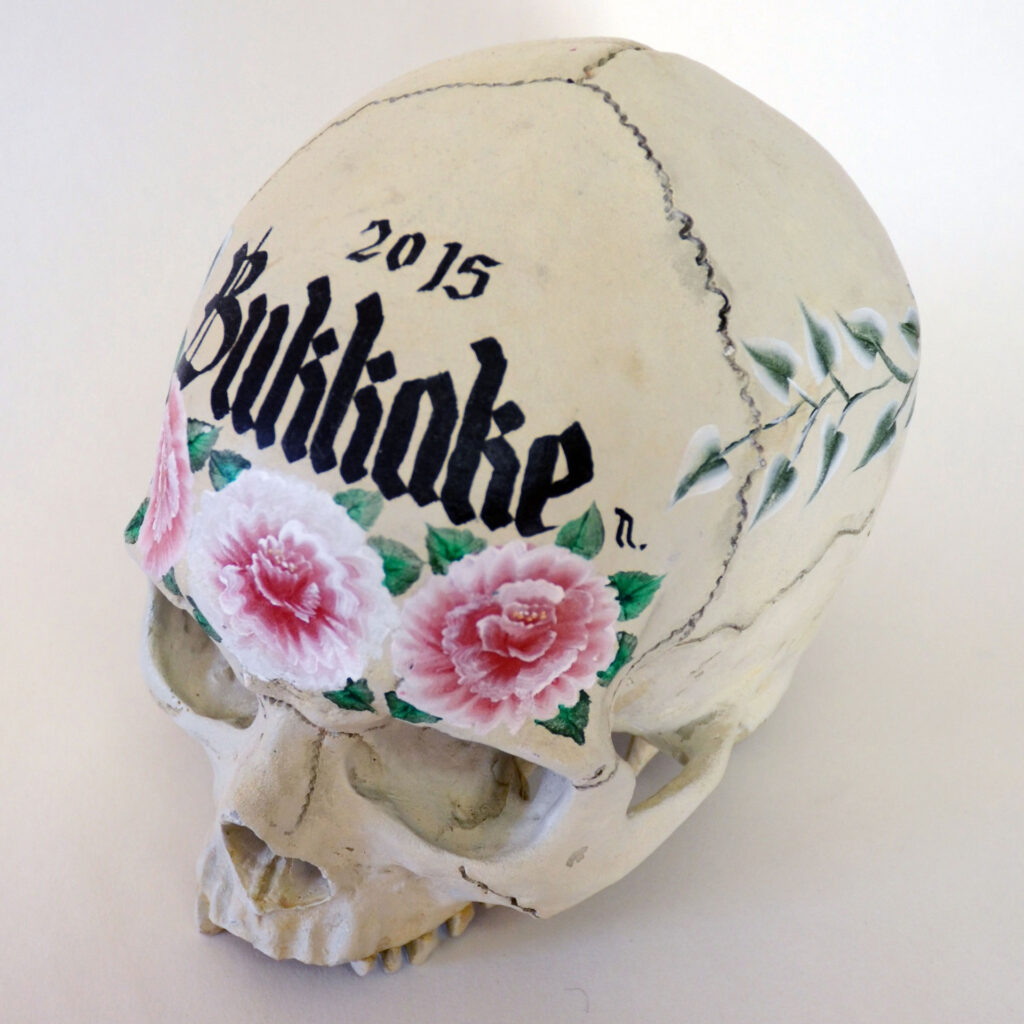

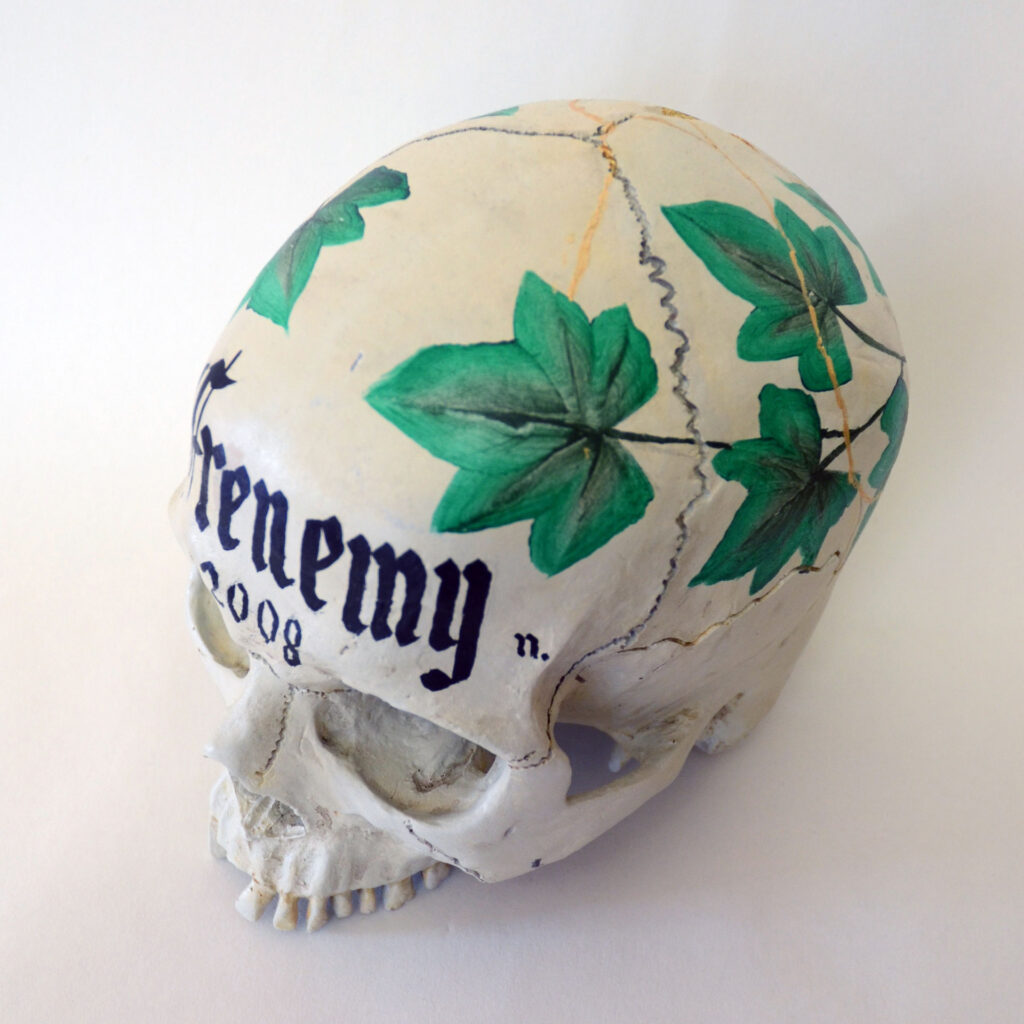

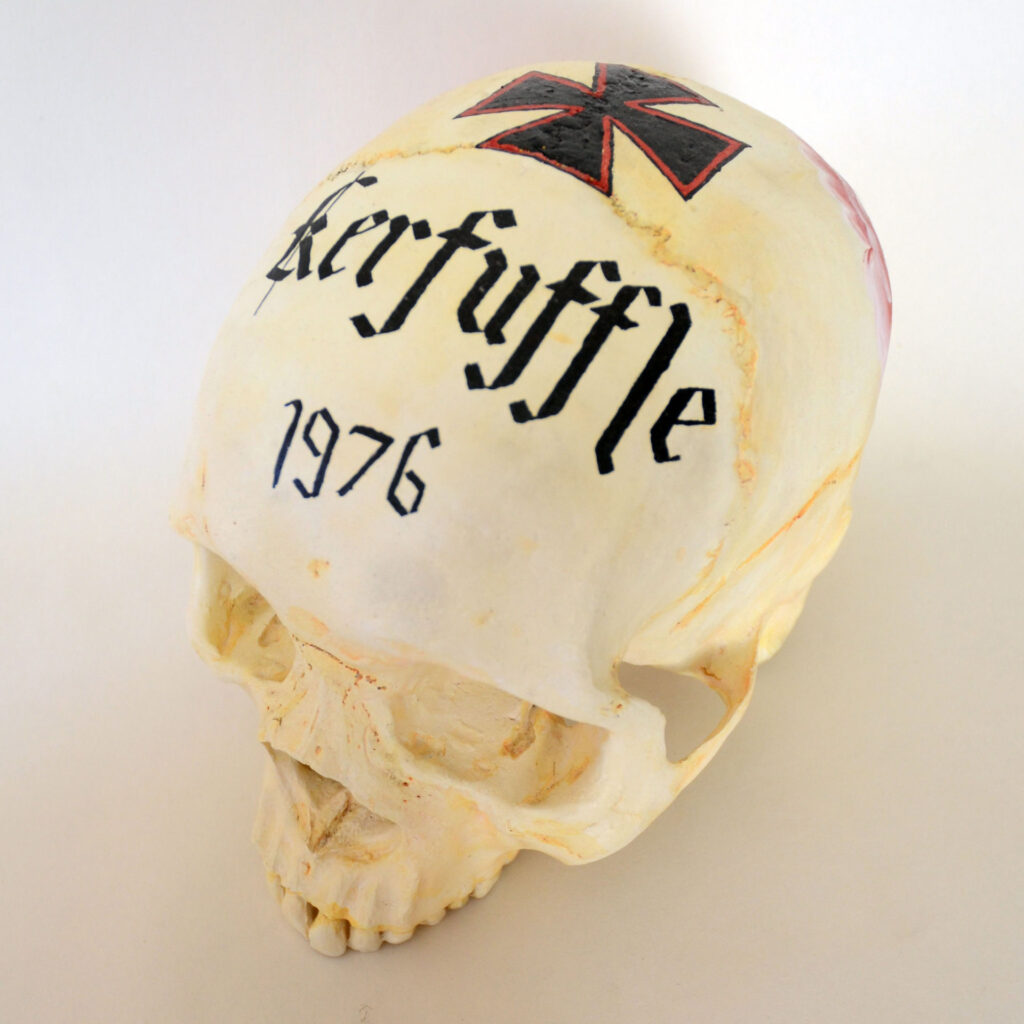

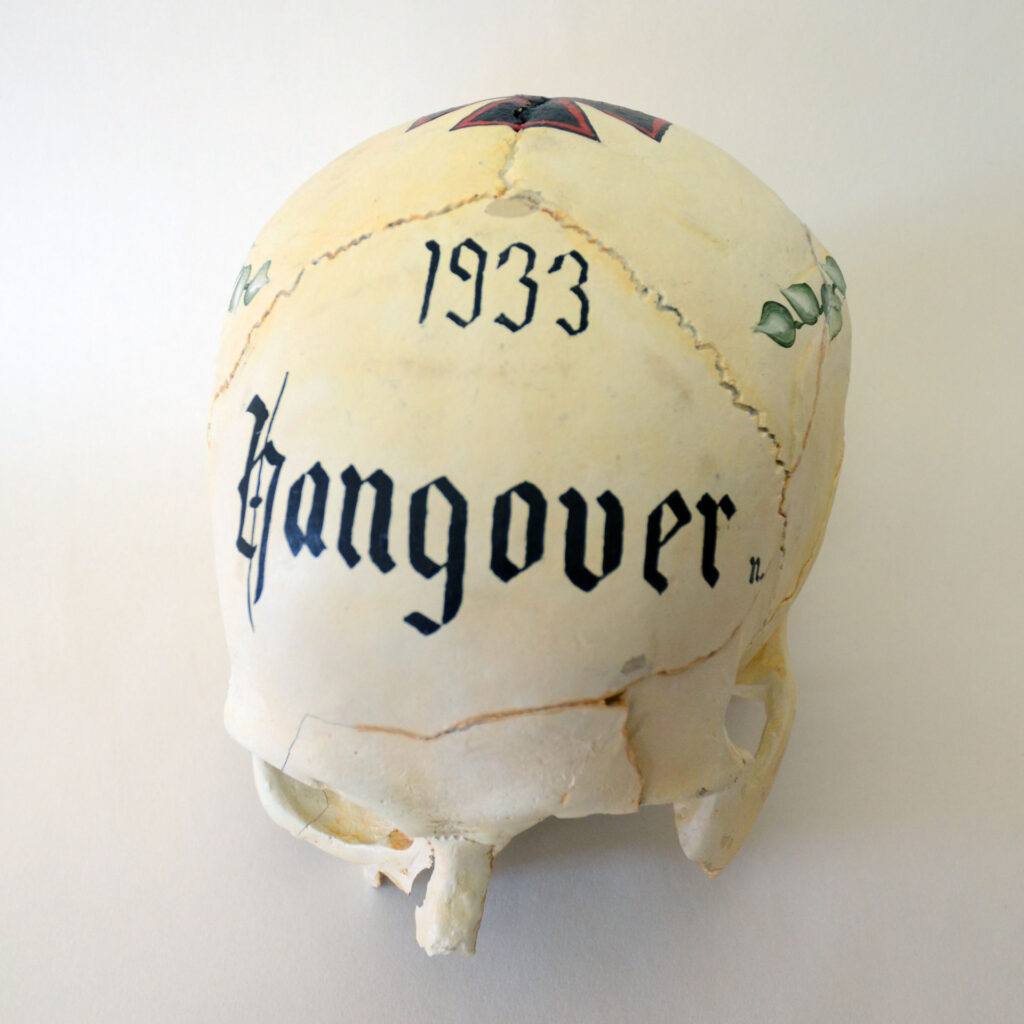

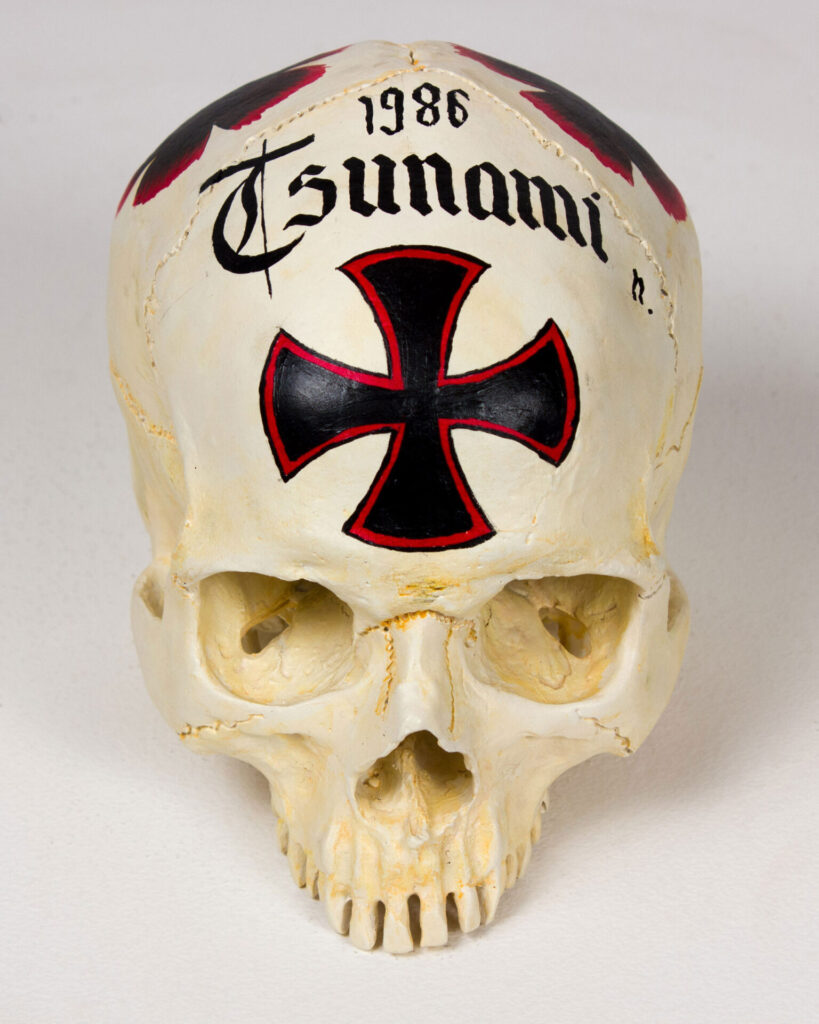

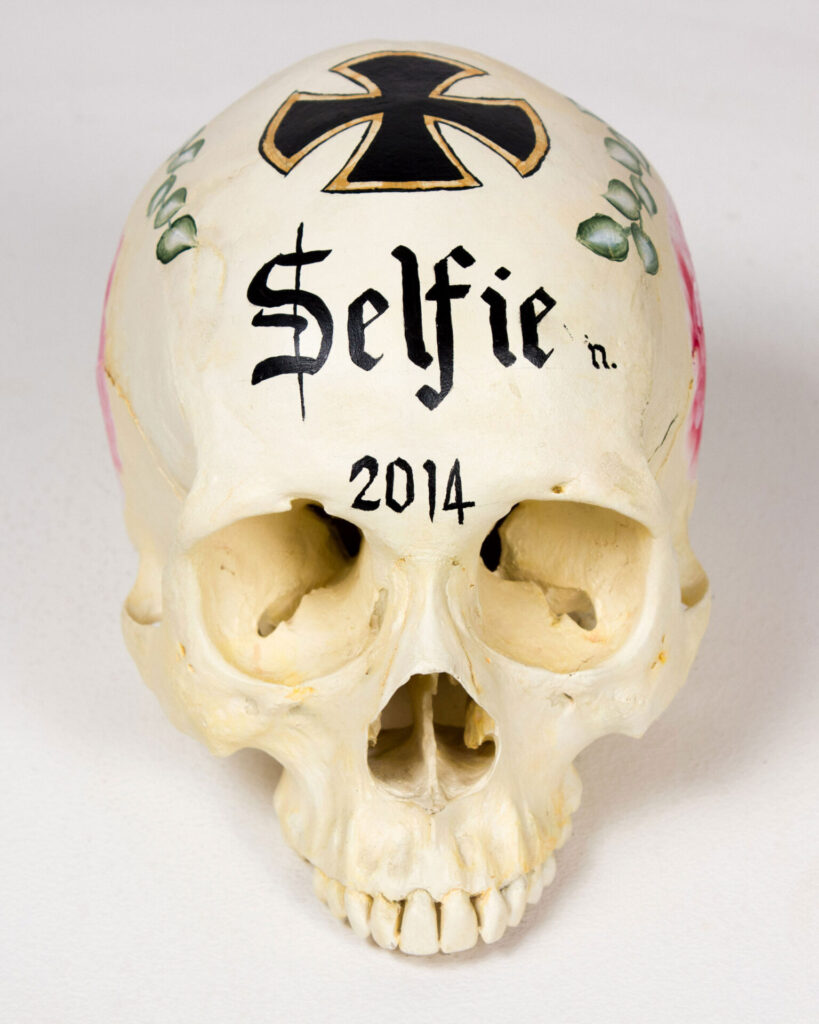

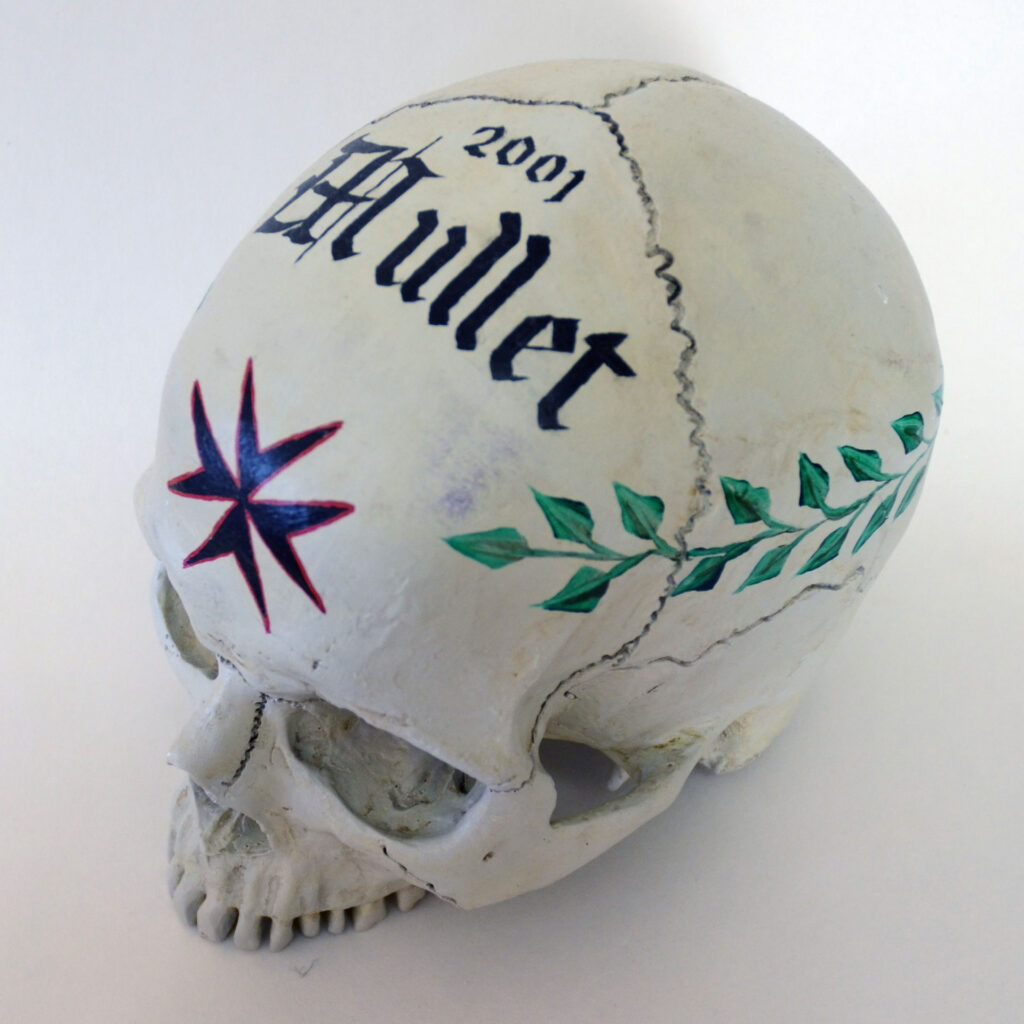

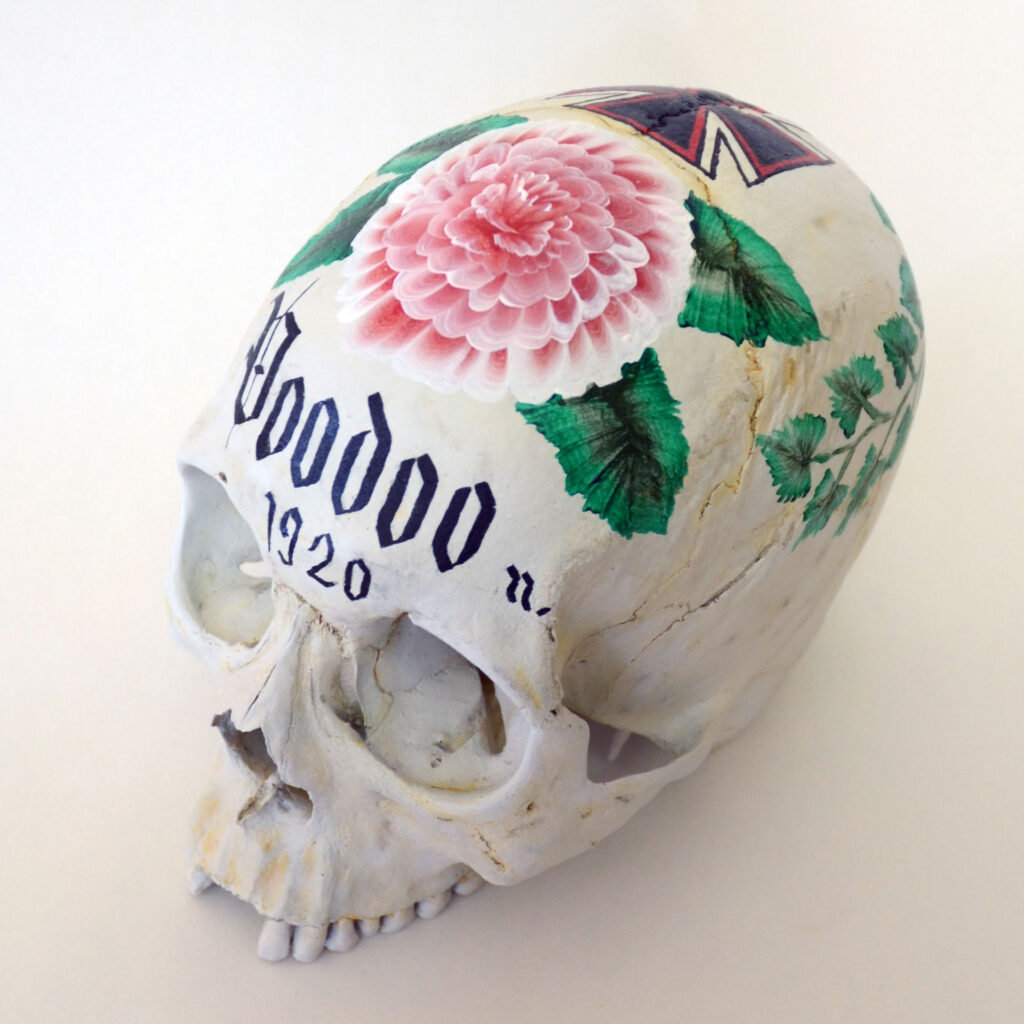

The situation reminded us of the Oxford English Dictionary’s quarterly lexicon update. Every three months there are headlines of what new stupid words the OED has added to its database. With the ease of a pale parent trying to talk Ebonics with their child, the OED keeps us up to date with new words that have hit the wires. There’s something unseemly about a publication whose first edition came out in 1884 documenting words like Bromance. Of course as new words are put into use, the dictionary must document this addition to fulfil its role as a repository of the English language. This combination of the hip and the Nanna got us thinking of the Halstatt Beinhaus of Austria.

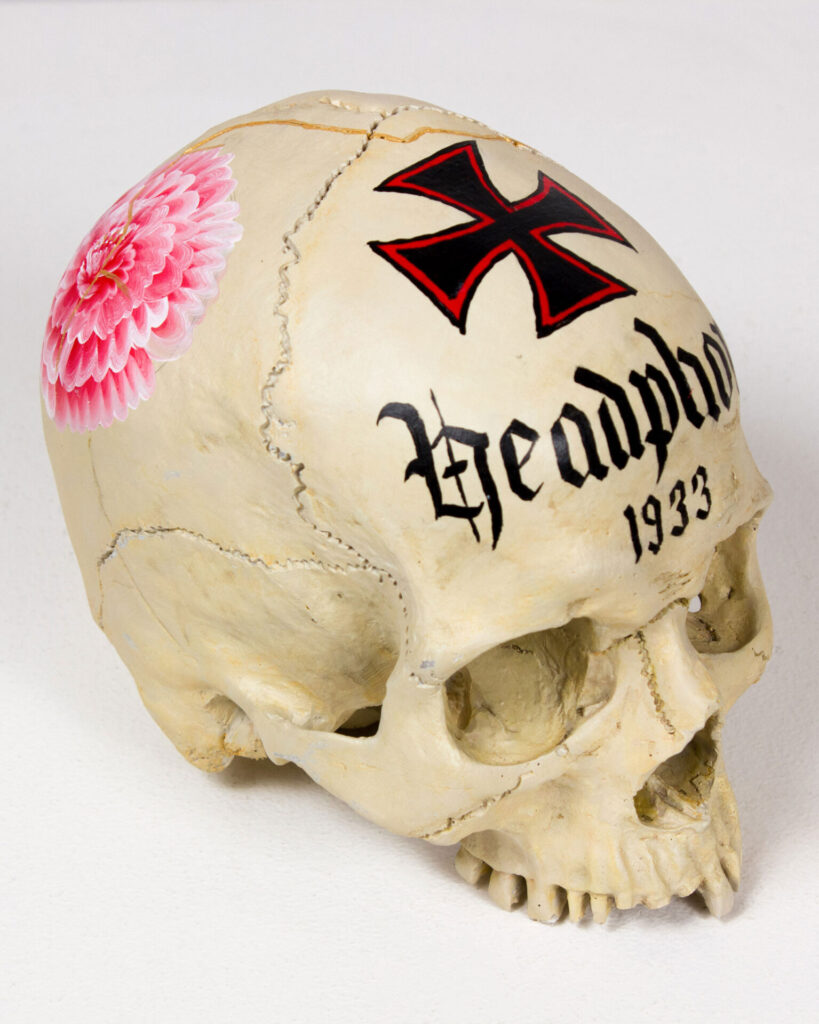

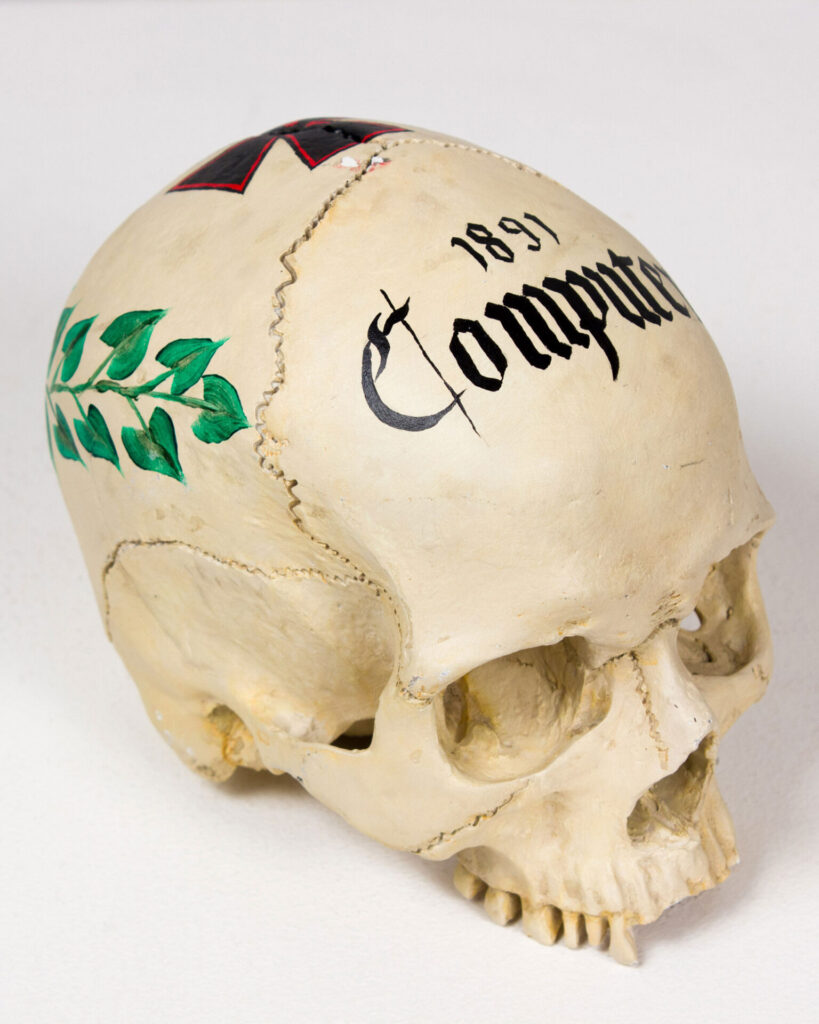

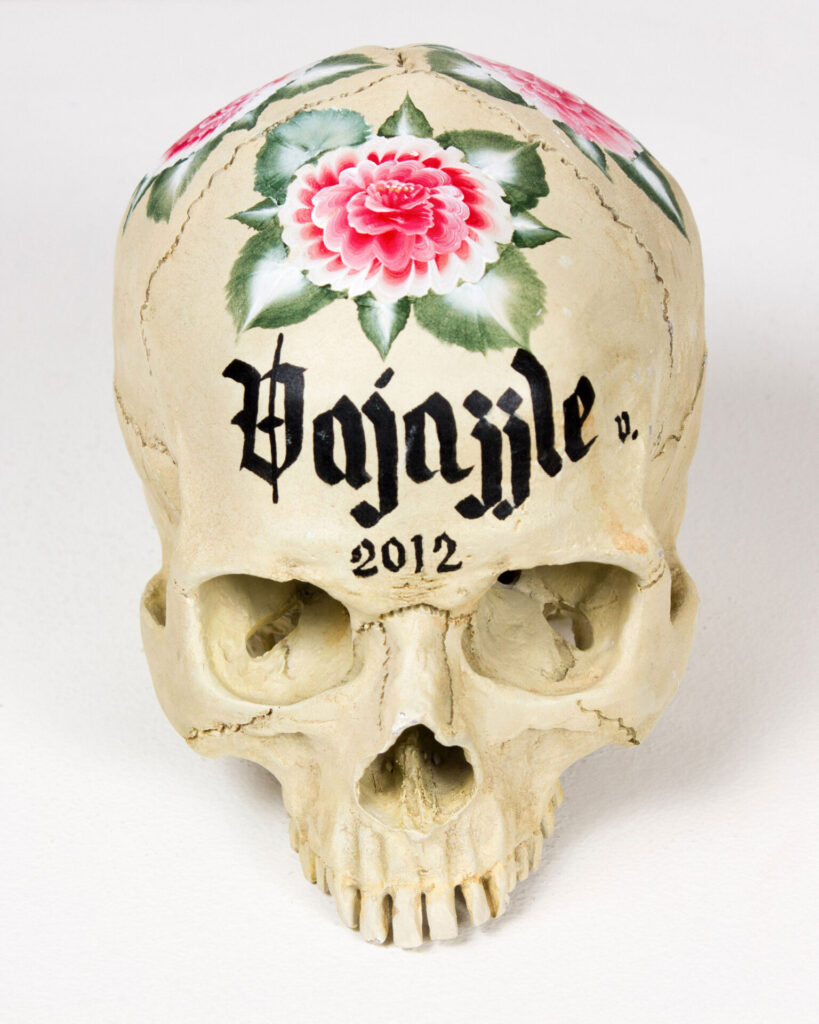

This charnel house exists to house the exhumed bones of the locals, as there is not enough land to bury the dead in the mountains. Traditionally each skull stored within the bone house has the name of the deceased written in Gothic script, the date of death and some kind of crucifix along with painted flowers or ivy ornamentation. It is an exquisite collision of black metal aesthetic meets Grandma’s blanket motifs.

For our skulls we replaced the proper noun with a choice word from the OED and the date of death was replaced by the date the word was entered into the English language lexicon. Placing the date on the skull suggests that the legitimisation of a facet of culture also heralds the conclusion of the word’s dynamic existence. Beginnings and endings become intertwined:

In turn, it is a mirror of the institutionalised culture that we strive to become part of: what was once edgy is integrated into the museological repository of the cultural establishment. The Daddy Danse Macabre continues….

This residency was made possible with support from Massey University, Wellington